Palo Alto Stanford Heritage

Palo Alto Stanford Heritage  |

|

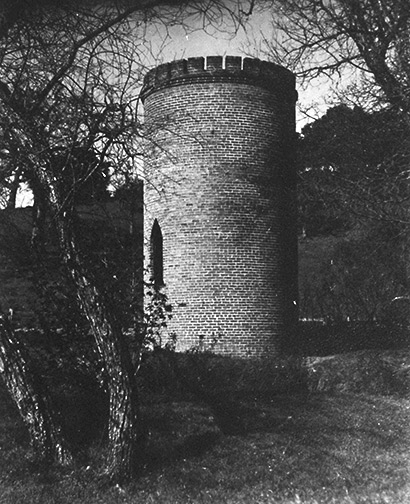

| Old photo of Peter Coutt's Towner (PAHA Archive) | Tower Library on Escondido Road |

Peter Coutts, a Frenchman whose real name was Jean Baptiste Paulin Caperon, purchased 1,400 acres of land in 1875 for $90,000 and sold it in 1882 to Leland Stanford for the bargain price of $140,000. In seven years of ownership, Coutts spent enormous amounts of money—some say $40,000 per year—and energy to transform his land into a showcase farm and ranch. He built Escondite Cottage as a temporary home for his invalid wife, their two children and the governess, Mlle. Clogenson. He also built a three–story Tower Library for his rare book collection. He was exotic, dignified, and generous, but evasive about his background. The residents of Mayfield appreciated his generous salaries and his insistence on paying for community events. Why then did Peter Coutts and his activities create so much conjecture and suspicion in his adopted community?

Initially, people were curious as to why title to his property and all business transactions were in Mlle. Clogenson’s name. Was she his mistress? Was his invalid wife, who was seldom seen in public, actually the Empress Eugenie? Was his obvious wealth gained nefariously? Rumor had it that Coutts had absconded with $5 million when he had served as the French army’s paymaster.

Two of Coutts’ projects on Matadero Ranch created the most intense speculation. One was the construction by a crew of Cornishmen of six long tunnels intended to supply sufficient water for his farm and for the artificial lake he had built. Sweating men dug hundreds of feet into the hills and removed tons of soil before finding a subterranean stream of sufficient flow. While the tunnels have been obliterated, remnants of the lake, such as an arched bridge, can still be seen east of Coronado between Mayfield and Gerona. Coutts followed this massive tunnel project by erecting a Normanesque red brick tower, fifty feet in height and circumference. Known as Frenchman’s Tower, it has no entry but has narrow arched windows and a crenelated top. It sits, mysterious and well preserved, on Old Page Mill Road. The construction of the tunnels and the tower fed the flame of local imagination. Surely the tunnels were escape passages or caches for Coutts’ ill–gotten wealth? And, wasn’t it likely that the tower was a watchtower or perhaps a fortress where food and ammunition was stored in preparation for a siege. These tales were so convincing that for decades Stanford students held exploration parties searching the tower and the hills for treasure.

The reality of Peter Coutts’s life and accomplishments is more mundane, more tragic, but no less fascinating than the legends. Born into wealth near Bordeaux, he was a classical scholar, bibliophile and a socialist. Coutts’ open opposition to Napoleon III’s policies and to the Franco–Prussian war led to a brief exile. Returning to France, he married and became a successful banker. One of his banks’ investments in Alsatian railroad stock became worthless after the Franco-Prussian war. In 1873, in order to escape Royalist attempts to control Bordeaux, he liquidated his Paris bank, paid off his customers and moved his family to Belgium, where he assumed the identity of a deceased cousin, Peter Coutts. The facts that Coutts never served in the army and that he was anti–Royalist give lie to the notion that his wife was an Empress or that he was a thieving Army paymaster. Protect his anonymity from his political enemies and to ensuring that his children inherited Rancho Matadero should he and his wife die, were the reasons that all financial matters were in the name of Mlle. Congeron. As for the six tunnels, it can only be said that farms and artificial lakes need water.

Coutts seemed genuinely contented on his Rancho with plans to build a large chateau. He counted many friends, whom he entertained lavishly. Why then did he depart with his family in such haste in 1881 and sell his property to Leland Stanford a year later? One of his friends, the French Consul–General Antoine Forest, disclosed to him that Royalist representatives of the defunct bank were trying to repossess his vast French land holdings. Coutts’s “disappearance” was essential to clear his name and have the liens against his property removed. Jean Baptiste Paulin Caperon’s return to France was bittersweet. In 1893, his 15 year old daughter, Marguerite was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The family moved to the healthier Evian les Bains on the French shore of Lake Geneva. There, Caperon built and furnished Chateau du Martelet only to have his beloved daughter die in 1885—the same year as the Stanfords’ son. Refusing to move into the chateau, Caperon visited his daughter’s grave daily until his death at the age of 67 in 1899.

Theories abound as to why Caperon built Frenchman’s Tower, but no one knows the reason. Perhaps, it was to be part of a grand entrance to the chateau on the hill. One thing is certain: Caperon has provided us with the most romantic architecture on the Stanford campus. You don’t have to be superstitious to feel a slight chill when looking at them.

PAST, October 25, 2013

E-mail us at either webmaster@pastheritage.org or president@pastheritage.org.

![]() Palo Alto Stanford Heritage—Dedicated to the preservation of Palo Alto's historic buildings.

Palo Alto Stanford Heritage—Dedicated to the preservation of Palo Alto's historic buildings.

Copyright © 2015 Palo Alto Stanford Heritage. All rights reserved.