Palo Alto Stanford Heritage

Palo Alto Stanford Heritage

When Leon Forrest Douglass purchased the Payne mansion in 1921 for $600,000, he was already a famous and prolific inventor of electronic, telephonic, phonographic and photographic devices. Upon moving into his new home with his wife, Victoria Adams and children, he marveled "I have traveled extensively abroad and I have never entered a more beautiful home." No expense had been spared in building the reinforced concrete residence nor in furnishing its fifty two rooms (see preceding article). The magnificent Italianate style landmark with its fifty acres of manicured grounds had been built between 1909–1914 for Mary O’Brien Payne and designed by the prominent San Francisco architect, William Curlett.

Douglass, was born in rural Nebraska in 1869 to Matie and Seymour Douglas, a millwright–carpenter. His father’s blindness forced him to leave school at age nine to support the family by running errands and apprenticing to a printer. As with today’s children and computers, Leon was fascinated by the cutting edge technology of telephones and, at thirteen, became one of the first telephone operators in Lincoln, Nebraska. Telephones, at this time, were marketed with phonographs and Douglass soon became infatuated by the latter. Too cumbersome and expensive for individual ownership, Douglass patented a coin–operated phonograph in 1886 and six years later invented a machine for duplicating phonograph cylinders earning him the title "Duplicate Doug." It was his spring motor device in 1894, however, which revolutionized the phonograph industry, led to the 1901 founding of the Victor Talking Machine Company in partnership with Eldridge Johnson and made Leon a fabulously wealthy man.

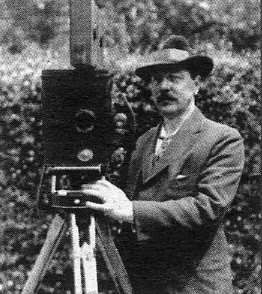

The Victor Talking Machine Company, later known as RCA Victor was named, according to Douglass, after his wife, Victoria, whom he’d married in 1897. Others think that Johnson chose the name to celebrate his engineering and legal triumphs. Whatever the derivation, it was as Vice President and General Manager at Victor, that Douglass proved himself an advertising genius. He popularized the image of the dog, Nipper listening to “his master’s voice” and greatly expanded the company’s advertising budget. He also developed and patented the cabinet and stand that became the Victrola, based on his belief that “…that ladies did not like mechanical looking things in their parlors.” Years of intense competition, travel and scientific work led in 1906 to a complete nervous and physical breakdown and a move to sunny California. Unable to work, Douglass began experimenting with color photography and in 1916 patented a process for filming in “natural color”, a forerunner of Technicolor. He retired from the Victor Company in 1921 when he purchased the Payne property. The new estate became his workshop and the site of important motion picture inventions, which would ultimately bring great pleasure to Americans during the Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression. The basement was filled with heavy machinery, and, on the first floor mezzanine, he installed a moving picture sound laboratory. The only exterior change to the house was the enclosure of a porch on the east side.

Douglass’ fortune and retirement led to patents as varied as: a zoom lens for motion picture cameras, improved radio receivers, the first anamorphic lens for undistorted wide–angle film photography, and devices for special effects such as appearing and disappearing ghosts, shrinking one actor in a scene, and the illusion of flames surrounding an actor. In 1918, he produced Cupid Angling, America’s first feature–length color film. It starred Ruth Roland, with Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks making guest appearances. By the mid–1920s, most of the major movie studios had contracts to rent his special effects cameras for $5,000 each per annum.

Victoria Manor and Menlo Park never saw a dull moment with this creative genius in residence. Douglass instructed Amadeo Gado, his landscaper, to cut a window in the wall of the above–ground pool through which he could film underwater swimmers. In one movie, his daughters, Ena and Florence swam with a seal and in another Florence wrestled an octopus. The latter episode made national headlines until journalists realized that the octopus was dead and its arms merely wired to Florence’s wrists with fishing tackle. Experiments with underwater cameras were also carried on in the pool.

Although Douglass was a modest and retiring man, his Christmas celebrations drew crowds from afar. From 1921 until 1934, town children attended a Christmas Day gala replete with the appearance of Santa Claus. The entire mansion was hung with garlands and wreaths as Saint Nick appeared on the roof next to the chimney. It was assumed erroneously that Douglass was Santa but the shy inventor merely watched joyfully from a second story window as children received dolls, books and sports equipment.

Two of Douglass’ daughters died in 1935, and Leon and Victoria moved to a modest bungalow on the property. During World War II, the mansion served as a convalescent home for patients from the nearby Dibble Hospital. The mansion and house were sold in 1945 to Menlo School who subsequently sub–divided the land but maintained the mansion for school purposes. The exterior of the house has changed little since its construction. Leon Douglass died in San Francisco in 1940 leaving a rich legacy of 50 patents, 24 of which were registered while he lived in Victoria Manor. ©

PAST, March 21, 2014

E-mail us at either webmaster@pastheritage.org or president@pastheritage.org.

![]() Palo Alto Stanford Heritage—Dedicated to the preservation of Palo Alto's historic buildings.

Palo Alto Stanford Heritage—Dedicated to the preservation of Palo Alto's historic buildings.

Copyright © 2015 Palo Alto Stanford Heritage. All rights reserved.