Palo Alto Stanford Heritage

Palo Alto Stanford Heritage |

|

When one approaches the house from the exterior, after first noting the softly graded dark to light pinkish tile roof and the mildly textured stucco, one must be impressed by the profusion of wrought iron. It starts right at the street. When you leave, study the carefully crafted gate with its painstakingly curved tendrils and, in the center, the hollow ellipsoid formed by a dozen small iron rods. Reflect that this wrought iron is, after all, iron — and it had to be heated red-hot and hammered endlessly to take its various forms.

|

|

Within the patio, wrought iron occurs in windows, the large door grilles, in the balcony, and is lovingly carried out in the front door handle. All of the iron work, except for the lighting fixtures, was made by Herman Bleibler, in a shop still carried on by his grandson on Page Hill Road. His love of his work can be seen in the hammering–out of the "spearheads" in the window grilles as well as the splaying–out and thinning–down of the little curls. Today they would all be the same thickness of metal and would not be splayed.

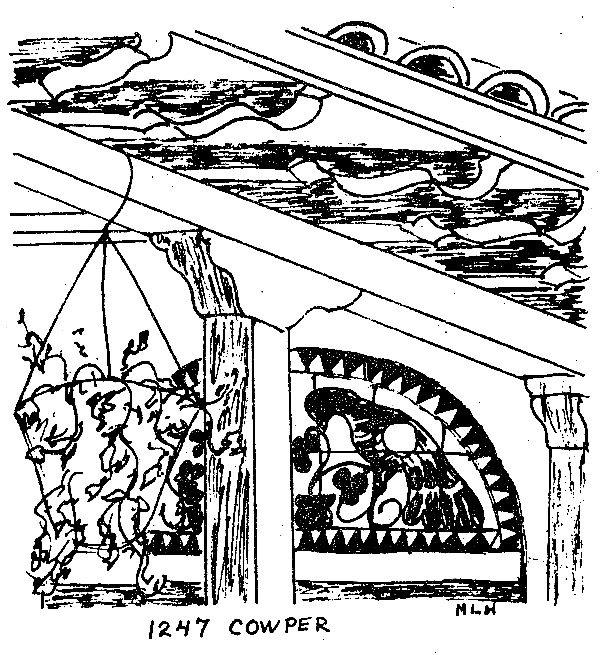

There is also a large amount of hand adzed and carved timbers in the cloister and in the overhanging balcony.

As one enters the patio, the chief impression is of vibrant and bouyant color, both from the flowers along the walks and in pots on the stepped-down railing of the outside stairs, and, from the tile of the two fountains — the wall fountain below the balcony and the center fountain. When Mrs. Norris was alive, the tinkling of the latter mingled with the high speed click of her typewriter coming from the open door above the fountain. Usually there was a colorful rug or shawl hanging over the wooden balcony. The tile over the front door with its softly muted colors was specially designed for the Norrises by A. L. Solon of San Jose who made all of the patio tile.

Inside the house through the paneled front door, again you will be aware of wrought iron, mostly in the spindles of the stairway and in the grilles which cover the recessed radiators. Here, though, the impression is more of softly textured plaster walls and a profusion of arches — one arch to the dining room, another to the living room and a third to the library. The doors were added later. The vaulted groined ceiling is the only one in the house. All the others are of heavy adzed wood timbers supporting plain boards. In the high–walled living room open trusses support the low–pitched roof as well as the wrought iron light fixtures. The gabled end (towards Cowper Street) is pierced by a small, deeply recessed sparkling stained glass window. All timber used in the ceilings and in the living room roof are load–bearing, solid Douglas fir, adzed, or rather carved, by a man winging a two–handled slightly–curved blade chisel as the timbers lay on a bench before him.

Wells Goodenough, the contractor, had several proud and highly skilled carpenters whose craftsmanship is still visible in the wood and doors of this building.

Unfortunately, in the nearly half century which has elapsed since it was first installed, successive coats of stain and paint have greatly obscured the original texture of the gray brown lightly stained wood. Paint has also covered the two-toned texture and coloring of the stucco walls, both inside and outside. This stucco, for many years unpainted, was formed of integral color; the plasterers first applied with a "loose wrist" a slightly rough layer of finish stucco in the approved color, and then in two or three minutes, struck the high places with a steel trowel. This produced a lighter finish on the smooth areas and a slightly darker, richer color in the depressed portions.

Obviously, hand work was not at the premium it is today. In 1928, while materials were costly, labor was relatively inexpensive. In fact very few artisans were getting more than a dollar and a quarter an hour. By 1928, this "Early California" style of architecture had produced a large number of indigenous mechanics, plasterers and carpenters who welcomed the opportunity to work on such a fine house as the Norrises.

The three fireplaces are typical of those used in this style of architecture, particularly the relatively simple one in the dining room. The living room fireplace of California tuffa is more elaborate, and the one in the library contains a design which was made with interlaced initials of the Norris family.

|

|

When Mrs. Norris was living in Saratoga, she had been able to have occasional barbecues for which she did the cooking. Now she found that in a four–servant house she was not exactly welcomed in the kitchen. And so, six years later—in 1934—the "Spanish kitchen" was designed and built. The roof tiles were originally visible through the strips on which they were laid. In storms, however, occasionally some water did come through and so it was recently decided to place the current plywood under the tile, which does not detract too much from the general appearance.

Both the main house and the "Spanish kitchen" received honor awards from the Northern California Chapter of A. I. A. and remain the largest and most expensive residence I designed in Palo Alto.

|

|

The Norrises

In 1927 Charles and Kathleen Norris lived in a home above Saratoga. They had come to feel that it was too isolated and too remote from San Francisco. Because of their profession, they could live anywhere, but after considering the entire state of California, as well as the French Riviera, Palo Alto was chosen. A real estate man showed them the recently completed Dunker home on Maple Street which charmed them, and Mr. Norris offered to write Mr. Dunker a check for $75,000 "right then", much to Mr. Dunker's distress, as he said that he had never before ''refused a profit" on anything he owned. However, Mr. Norris did what only too rarely happens to architects; he went out and got the same architect to design the home on Cowper Street. Actually, as the plans worked out, the Dunker house would have been much too small. I worked primarily with Charles, though Kathleen acted as a restraining influence. They had not wanted the house to cost over $100,000, which was about like saying $500,000 today, so she urged omitting a billiard room which projected as a wing. (Later it was added under the garage.) Charles and Kathleen Norris were both authors. Mrs. Norris' work was very popular and "Collier's" paid $50,000 per continued story which were aimed at the "working girl." They were moral; virtue always triumphed in the end. There were no "Abby van Burens" running letters and answers in the daily papers in those days, so Mrs. Norris received many letters from hard-working young women with problems. Feeling it was her duty to reply, she wrote personal answers on her typewriter. Charles Norris, on the other hand, wrote serious books such as Seed and Hands. They were successful, but not to the extent of Kathleen's.

Mrs. Norris wrote upstairs in the room opening into the patio directly above the fountain. Anyone coming to the front door in the morning could hear the high speed clicking of her typewriter. She merely dropped the pages on the floor and they were picked up by Mr. Norris or Walter McClelland, his secretary, and proofread and also checked for such errors as a character having red hair in the first chapter and being a brunette later on. Mr. Norris wrote in his study very laboriously, often spending a whole day on a half page, writing and rewriting and still being frustrated and feeling that he did not convey just what he wanted.

|

|

|

|

E-mail us at either webmaster@pastheritage.org or president@pastheritage.org.

![]() Palo Alto Stanford Heritage—Dedicated to the preservation of Palo Alto's historic buildings.

Palo Alto Stanford Heritage—Dedicated to the preservation of Palo Alto's historic buildings.

Copyright © 2015 Palo Alto Stanford Heritage. All rights reserved.