Palo Alto Stanford Heritage

Palo Alto Stanford Heritage

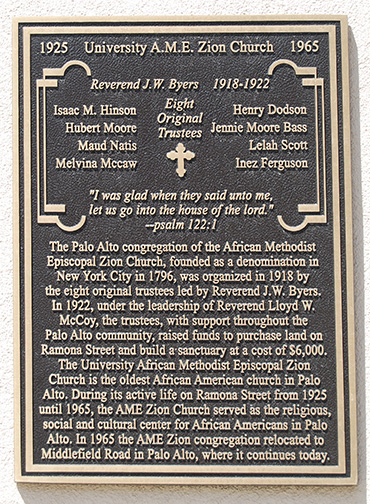

The University AME Zion Church was founded in 1918. It was the first African–American church between San Mateo and San Jose. Its 22 congregants met at Fraternal Hall until they were able to purchase land on Ramona Street. Funds were raised throughout the town for a new church, which was [build in 1924 and] dedicated April 5, 1925.

There is something comforting about the simplicity of AME Zion’s architecture. Modified Classical Revival in style, with minimal detail, it has charm and character. The one story stucco building, with its steep, front–facing gabled roof, has a raked cornice at the eaves. A hipped roof bell tower rises from a gable side. Broad steps lead to an enclosed porch through a classic elliptical arch. The arch detail is repeated in the stained glass window to the right. Above it is a stained glass gable window in an unusual triangular design imitative of the AME Zion logo.

Entering the main church door, one finds a large room whose fir floors glow with light filtered through the stained glass windows. These double hung windows have none of the brilliant colors or religious scenes common to church windows, yet their pastel hued color and simple rectangular and diamond shapes create a serene, contemplative atmosphere.

819 Ramona’s neighborhood straddled the area between Palo Alto’s downtown businesses and Professorville’s residences. Service providers such as lumber yards, laundries, automobile dealerships, plumbing stores and bakeries commingled peacefully with the homes of the working classes. It seemed like the ideal setting for AME Zion. According to Feliz Natis, whose mother was a founding member, “…there weren't many blacks around. The church was one of the few places we went. It became a center for us to get together." Tennessean, Doris Richmond, a member of AME Zion since 1949 and a Tall Tree Award recipient, recalls that in Palo Alto “Everything was impressive. The people were friendly, so much like home.” From its inception, Palo Alto has considered itself a liberal haven although the town’s black population never rose above two percent. In some respects, however, Palo Alto proved no different from Anywhere, U.S.A.

In 1920, the Palo Alto Chamber of Commerce, supported by the Palo Alto Times, the Native Sons of the Golden West, the American Legion and the Palo Alto Carpenters Union, passed a resolution calling for a “segregated district for the Oriental and colored people of the city.” Henry Dodson, the president of the Colored Citizens Club of Palo Alto, responded to the segregationists in a tone reminiscent of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: “Shame on a race that…holds in its hands the wealth of the continent and yet refuses to lift its less fortunate fellow man….” Racial zones were suggested again in the 1940’s but never legislated.

Post World War II saw an influx of southern blacks to the Bay Area. In Palo Alto, their houses were concentrated along Fife Street, El Capitan Road and on Ramona Street, near their church. From 1925 to 1950 most racial discrimination was insidious, in the form of residential subdivision covenants banning persons of color. Joseph Eichler was an exception; he resigned from the National Board of Realtors to protest their discriminatory policies. Federal Housing Association manuals instructed banks to avoid mortgages in neighborhoods with "inharmonious racial groups" and suggested that cities enact racially restrictive zoning ordinances. Palo Alto’s Board of Realtors president offered a flip justification: “If you do sell to Negroes, everyone else is down your throat.”

A not so insidious demonstration of intolerance occurred on May 31, 1946 about 100 feet from AME Zion church. Early risers were shocked to find a three foot long Ku Klux Klan insignia painted in the intersection of Ramona and Homer. Police Chief Howard Zink felt the graffiti were done “by an organization, not by pranksters.” Yet, these efforts to define who belongs and who doesn’t belong seem ironic when we consider Ruth Anne Grey. Her great–great grandfather, a former slave from North Carolina, moved to Palo Alto in 1887. Her grandfather was a founder, and she a trustee, of AME Zion. Her family's local presence predates Palo Alto as a city and Stanford as a university.

There have also been episodes of racial brotherhood and tolerance. During the height of the depression, when AME Zion faced foreclosure on its $6,000 mortgage, Palo Altans rose to the occasion. Every bank in town opened accounts to collect donations, churches held fundraisers and private individuals donated generously. By 1939, the mortgage was paid off.

After forty years at 819 Ramona Street, AME Zion moved to a larger facility at 3549 Middlefield Road. Sold to the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, the old church deteriorated. A successful battle to prevent demolition resulted in restoration for adaptive reuse in 1985. Now, a Zumba beat has replaced choral music. The AME Zion Church was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1996. ©

PAST, January 24, 2014

E-mail us at either webmaster@pastheritage.org or president@pastheritage.org.

![]() Palo Alto Stanford Heritage—Dedicated to the preservation of Palo Alto's historic buildings.

Palo Alto Stanford Heritage—Dedicated to the preservation of Palo Alto's historic buildings.

Copyright © 2015 Palo Alto Stanford Heritage. All rights reserved.